SPECIAL REPORT: End of an era as Spinningfields completes

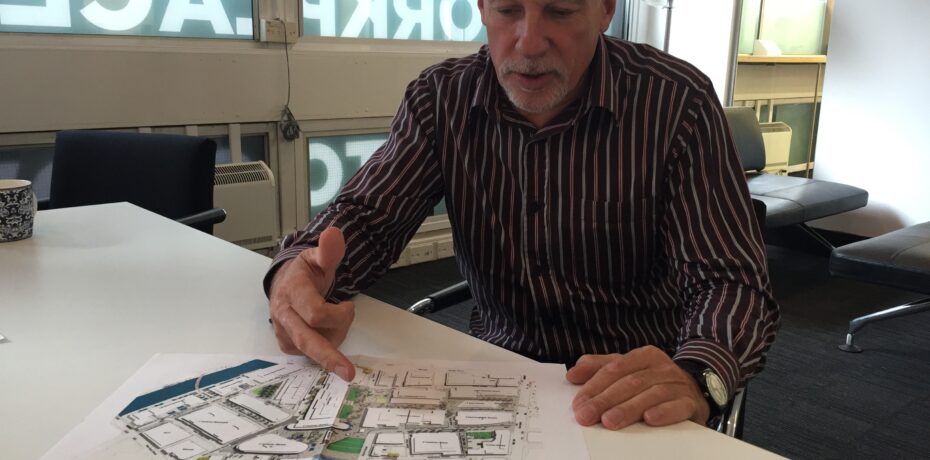

Twenty years ago, Allied London made its first purchase in a rundown area off Deansgate to assemble land for a new business district. Last week the final office building at Spinningfields sold for £200m. Graham Skinner, development director of Allied London, sat down with Paul Unger to tell the inside story of this peerless and pivotal project in Manchester’s economic regeneration.

1997

Mike Ingall, chief executive of Allied London, and Sir Howard Bernstein, chief executive of Manchester City Council, started discussing the transformation of an unloved and fragmented area of the city centre after being introduced by property advisor Bob Dyson of Dunlop Heywood.

Graham Skinner explains: Allied London, in discussions with the city council, started buying assets, particularly Deans Court, part of the warren of offices that included the old Manchester Evening News’ black building on the front of Deansgate, and two doughnut-shaped buildings behind. At the time there was a vision for the unloved side of Deansgate between Bridge Street and Quay Street, and part of that vision was to open the city to the river. There was a huge contiguous block in the way, the Crown Court was connected to the Magistrates’ Court and you could only get so far into the area. You couldn’t get really beyond Hardman Street and if you wanted to go to the college, you went down Quay Street or down Bridge Street and in. Because it wasn’t that permeable, it wasn’t that safe and it just wasn’t a particularly loved area, even though it fronted Deansgate. So, the city had this plan, the only way to open up the river was to actually demolish the Magistrates’ Court which would mean building a new Magistrates’ Court and that’s where the concept was spawned with Allied to do a land swap and put a Magistrates’ Court on Allied London land, demolishing part of Deans Court and creating the space where the court is now, for a central node of public pedestrian ways which is now Hardman Square.

Allied London and the council spent four years working on the masterplan. The city worked with Allied to acquire strips of land where needed to deliver a comprehensive masterplan. The elements the city wanted were job creation and this meant the quality of buildings that might attract occupiers from London. The other thing the city wanted was public realm. Spinningfields was pretty hot off the back of the IRA bomb and the city understood what they were able to do with modern masterplanning. There are very few public squares in Manchester because it was a Victorian street grid. So Allied London’s response was to move away from the old four storeys plus a mansard [dormer roof extension] which had been the planning regime up until that time.

The masterplan has barely changed over the 20 years. One Spinningfields Square, the RBS building fronting Deansgate, was going to be a hotel, but that was a 20,000 sq ft floor plate so it was easily adapted to offices. 2 Hardman Street, the Guardian Media Group moved there with Deloitte, another 20,000 sq ft floor plate. And you start to see on the masterplan; 20,000 sq ft allows 200 people per floor rather than the small warren buildings that have been available in Manchester.

The masterplan was developed with masses of documentation to say how well these buildings would be designed, what the spaces would look like, the way we would treat plots as and when we demolished a block, that we’d do temporary public realms as we did in Hardman Square, as we did where the MediaCom building now sits in Hardman Street.

2001

Manchester College’s new home on Quay Street was the first building completed, relocating from an old campus along the river, but it wasn’t until the first major office prelet that Spinningfields grabbed the attention of the office market.

Skinner: Eventually there was a prelet in 2001, a re-grouping of Royal Bank of Scotland facilities. They did one in London, they did one in Birmingham and they were doing one in Manchester to bring all the smaller offices together. It was massive for Manchester; 400,000 sq ft in a non-customer facing building which they took at 1 Hardman Boulevard, so the masterplan simply joined two buildings, and then the customer-facing building they wanted on Deansgate. They were signing up for approximately half and wanted to stay rigidly to the 20,000 sq ft and the right scale. Then Fred Goodwin [chief executive of RBS] decided ‘No’ he wanted to brand the building and he took the full building. It ended up at 520,000 sq ft net prelet for the two buildings.

The RBS deal launched Spinningfields and showed the world that Spinningfields was real. It didn’t totally persuade some dyed-in-the-wool agents at the time that believed the Manchester [office] market was always going to be King Street and Spring Gardens and it would never go further than that but, you know, good job somebody did have some vision really.

Close on the back of RBS we then got other prelets and I think it shows if you work hard and you go for the right quality standards then you create your own luck because a Civil Justice Centre then appeared as a national enquiry and we said we could do it. We didn’t own the land which it was on but we made a play for the Civil Justice Centre, got ourselves into a good position but we had to acquire the old Gartside Street car park to make way for it, build the Spinningfields car park on Quay Street and then we were able to build the Civil Justice Centre. It started as a potential PFI but we wrestled that into a standard landlord and tenant property arrangement. By that time, Spinningfields was known.

It was a live site, there were occupiers in all the existing buildings. When we demolished Deans Court, we demolished half of it to build the Magistrates’ Court. We still had the Guardian Media Group, or the Evening News as we know them, in a building that was connected with a doughnut building and it was only when we built 2 Hardman Street that we could move the Guardian Media Group out to allow us to build 3 Street and then The Avenue. All Spinningfields was like that; it was a team with a ladle type of operation.

And, at the same time as we did that, we also built 3 and 4 Hardman Square. The new Magistrates’ Court had opened and an access way passed John Rylands Library, which was also being extended at the time to create the coffee bar. We were then able to get our hands on Hardman Square. We brought in Fosters to do the design. It had to be a north-south pivotal route and it had to be an east-west pivotal route. It was going to be the heart of Spinningfields in order to offer the route down to the river, subject to building a bridge that came a little bit later, a route to Salford Central Station.

3 Hardman Square was the famed Halliwells preletting and 4 Hardman Square was built speculatively off the finance we were able to raise for the Halliwells’ prelet but they were let during the build period to HSBC and Grant Thornton.

2006

As Spinningfields gathered pace, Allied London became more ambitious – although certain agents, even those instructed on Spinningfields, urged caution.

Skinner: Strange developer Allied London. We get planning consents and then we go back to make them smaller. 3 Hardman Street was going to be over 400,000 sq ft net, and I remember we had a meeting with an agent, Ken Bishop of DTZ, and he titled the meeting ‘Sense or Suicide’. Shall we go for that much space? Is it too much of a gamble? We were in the market for a prelet that required that we build the building incredibly quickly, the prelet was to Barclays. At that time, we went back through planning to knock a couple of floors off the building; one to assist the speed of build, and the other, let’s just be wary, we might be getting a bit giddy. It was still the largest speculative building ever built outside London, 350,000 sq ft net offices, another 25,000 sq ft of retail and, with the car parking, it was close to 500,000 sq ft of development.

3 Street has a story in itself; we had the 80,000 sq ft pre-let to Barclays with options to take further space, an extra couple of floors, to give them a real sort of North West hub. Shortly after letting the space to them and the financial crisis unfolding in 2007, we saw in the press that Barclays were going to offshore which left us with a problem; we had a safe bankable prelet, but we could potentially have 80,000 sq ft of space in competition with the rest of the space we were trying to let.

It was an extremely tense time. We were going into recession, and this again is where Allied London do have a large tendency to create their own luck. The building was just way better specified than anything in Britain. We benchmarked it against the very best in London, any Bishopsgate type developments. We ensured that we had three-metre ceilings rather than 2.7 metres, we had every bit of mechanical engineering you could have in the building. We didn’t know what the new building regs were going to be; they knew it was going to be about carbon reduction. We set off to achieve the later building regs without knowing what they were so we went for 40% whereas building regs were only 20% so we had a future-proof building with superb specifications inside. The three-metre ceilings, the size of the floor plates and, even though 2009/10 the world was a dire place, the space just shot off the shelf. Everyone that came to look at the building said, ‘This is it, we’re coming here,’ and of course, we built void periods into the appraisal because we didn’t expect to let it all within a year or two so we were able to give pretty good incentives to people. We built it out even in 2009/10, they were probably our best letting years at Spinningfields, and we built it out as per the original appraisal. The main lettings guy was Trevor Sloan at Jones Lang LaSalle.

Eventually we renegotiated with Barclays, who then took a floor of the building for the higher end side of the bank and, during that period, we collected a few prelets en route.

At the end of 2008, Spinningfields was pretty much still yellow, it was more hi-vis jackets than suits. There wasn’t any retail because we’d not opened any yet. Mike started animating the area, took on a team of people to do it. I’ve got to say we didn’t have that much spare cash so introducing an outdoor film screen and running a screen and running an ice rink were a burden at the time. But we soon learned how to commercialise those areas and create some further dwell time after the screen finished and it did coincide then with the opening of The Alchemist. It was a couple of years of sheer hard work and, I think it’s fair to say, that hard work hasn’t stopped. Mike always wants to be beyond that curve… If he’s seen something on his travels, if he has an idea then he’ll bring it back and we’ll trial things and just try to be the first at doing something.

Stuart Lyell [managing director of Allied London Development Management] and myself were letting all the retail as well because when we’d built 3 Hardman Street we’d built the other half of the street from the Magistrates’ Court so, at long last, we could let The Avenue as retail space and all developers were becoming more focussed on sweating their assets. We’d left retail spaces alone until we’d got enough public realm to get the mix that we wanted and at that point we’d just got the mix just as the market was going sour. We’d done a letting to Armani, we’d done a letting to Mulberry, we’d done a letting to Flannels. The Avenue was intended to be Manchester’s Bond Street. We had names attached to every other unit and a few names attached to some, people that hadn’t ever been in Manchester before. Some were concessions that ceased to be concessions and moved out and opened their own stores but they started collapsing like nine pins in 2009/10 and just stopping any sort of acquisition, even their overseas acquisitions were stopping. The street, as you know, then developed into more of a restaurant and retail hybrid.

We created all the retail spaces double height, eight metres high, all capable of taking mezzanine floors – that was part of the Spinningfields initial design and implementation guide. The flexibility and engineering of the buildings enabled us to fill them with food and beverage outlets that probably wouldn’t fit in a number of buildings elsewhere.

At Left Bank, we did restaurant lettings to venture funded food and beverage chains that just needed to open at a rate. They were good covenants and they were offering good rent and we probably took our eye off the ball in terms of the mix of uses and so forth. And then the recession gave us time to look again and start getting into who the local operators were and who might be able to do something that was more akin to Manchester, to mix those more institutional retailers up a little bit and that’s probably where the relationship started with Mike Ingall and Tim Bacon [late founder and owner of Living Ventures] and the introduction of the various Living Ventures outlets that surround Spinningfields. And many of their brands were experiments, using money from Allied London to start them and trial them and they’ve now gone on to spawn actual businesses; The Botanist comes out of the Oast House. The Alchemist was the first bar that we opened in Spinningfields which now has grand identity of its own.

2010

In March 2010, the council assisted Allied London through the market doldrums, buying the final two plots for £15m and leasing them back to the developer in return for an agreement to resume construction by 2015. These plots would become the 160,000 sq ft XYZ – briefly called i+ and Cotton Building during planning – where the money has been repaid, and No1 Spinningfields, 340,000 sq ft, for which the council is due to be repaid after the Schroders deal completes.

Skinner: The support we’ve had from the city has, from day one, been awesome. We’ve had the financial support, the backing through recession, whereby they acquired the site, we paid them rent on that site and gave them a return on it until such time as we could buy it back but the support through Spinningfields was at every level in the city council. To develop a site of this stature, we dealt with Environmental Health, we dealt with Highways, with Operational Services, with Planning, Building Regs. But we’ve always had support, literally within 24 hours of asking for it by a head of a department. It’s the best partnership I’ve been involved with and I’ve worked in a lot of public and private partnerships. I do recall Howard saying the same at one point that it was the best that he’d worked with. And it truly was a partnership.

2013

Public loans were provided by the EU’s Evergreen urban development fund for XYZ, which received £10m, followed in 2015 by £12m for development of No1, alongside bank debt.

Skinner: I don’t think there would be need for that public funding in Spinningfields now. There was in 2013. There was just nothing happening in the market at all and without that we wouldn’t have got XYZ going. So, it was very useful cash, and it’s been repaid, and it did exactly what it says on the Evergreen can. It did what it should do. They were then keen to have the same success and put some money into 1 Spinningfields. Did we need it? It was useful to have but we were probably up and going again by that stage. And we were building quarter of a million feet with just 50,000 pre-let. Spinningfields certainly wouldn’t need it now, but a site the size of St John’s or some of the peripheral sites around Manchester, they may still need that money, certainly if they are contemplating building speculatively.

2017:

Spinningfields today totals 4m sq ft, of which 2m sq ft is offices, 200,000 sq ft retail and leisure, and there are 400 apartments. Around 200 companies are based there.

There’s a quote on the wall that greets guests to Allied London’s office at Old Granada Studios when they step out of the lift, about being a prophet …and it seems apt at the end of the development to reflect on that. Has it turned out how you envisaged?

Skinner: The quote’s an absolute Ingall-ism. He aspires to see way beyond the curve – 10 years, 15 years into the future. You can’t always do that but that’s just to tell the architects that ‘If you’re going to come in our office and suggest something…,’ that’s a bit of a reminder of the way they should approach it.

Spinningfields in terms of the size of the buildings to attract the occupiers, yes I think that’s worked. I would have preferred to see more relocations from London; there have been some. The Civil Justice Centre was a national enquiry and quite a bit of space that other occupiers took was used to bring staff from London. We signed PwC recently as a pre-let for No1 at 50,000 sq ft, they’ve now got nearly 100,000 sq ft and they see it as their flagship building, and they’re able to steer international clients to meet in Manchester.

What we wouldn’t have envisaged is the food and beverage and the way that’s taken off but if you build buildings of the right quality and the public realm of the right quality then you create your own luck. I think we’ve done five or six restaurants and then there was a list of restaurants out of London that were either going overseas, of if it was the UK, it was Spinningfields; it wasn’t Birmingham and Manchester; it was Spinningfields. And we heard that from several people so hopefully next will be St Johns.

How has the office market changed in the past 20 years?

I think from a property occupation perspective, in 2010/11, when we were saying ‘what’s going to happen next’ and we’d not built anything major for a few years, we saw a change in fashion. When we did Manchester House, [now Tower 12] we kitted it out with exposed M&E and so forth and we moved away from the historic blue carpets and suspended ceilings, that was a sea change and I think it’s fair to say a lot of people have copied that since.

When we’d done that and we were looking at XYZ and what this building should be. We decided to make it a flatted factory with uber-resilience within the building; very liquid, and we thought people might occupy it more densely than they’d occupied in the past. The British Council for Offices is still suggesting one person per 10 metre squared or even one per 12 metre squared, and we saw people maybe going to one per six to seven so we built XYZ with this flexibility in it and, lo and behold, people are occupying at one person per six at day one. We’ve had similar parallels with No.1 Spinningfields where people are occupying more densely to save costs. If you save on the square footage, you save on the service charge, you save on the rates, so a lot of people now are focusing far more business-led, cost-led on their requirements and they’re also, in parallel with that, all about staff retention. They’re looking absolutely at amenity and the amenity available and fortunately, on the Spinningfields campus, we have that amenity but, even so, we’re putting amenity into the buildings so both the XYZ building and No.1 Spinningfields have a floor taken to a business lounge where, if you’re in the building, you can go there, you can use it as a conference room, you can socialise and that is probably something we wouldn’t develop a building without that any more.

You learn from recessions. Good things came out of recession, you know, I think just being a little bit more careful and thinking through what we’re doing, we wouldn’t make the decision we made when we did Left Bank just to take a series of relatively bland occupiers just because they filled the space. We’re far more careful now. Even if we had a list of a few occupiers, we’d be interviewing them on what they were going to do and how they were going to do it as opposed to just the rent and the covenant. We’d probably take more risks on the covenant to get the right occupier. That’s been happening. Again, Mike is very close to this, and it’s not close to his chest, he keeps it close to his heart.

What would we do differently? There’s some things we spent money on where we could be a little bit more careful next time. We had to move contractors round an awful lot, which is money in itself. A lot of the temporary works we did. There’s an opportunity at St Johns, we could do that more holistically. But no, there’s very little from 2002 to now we’d change other than this focus on the occupiers, because it’s all about the occupiers and it’s about their experience about their businesses, and their businesses functioning and hopefully growing.

Internationalism

I’m a Mancunian. I probably couldn’t have done Spinningfields had I not had an earlier career overseas. I worked for Westfield for some years in Australia and built the Hotel Arts in Barcelona. But to come back and to deliver a site of this stature and this size in my home city, my kids have grown up through that period and have seen it, I’ve got a lot of personal pride in Spinningfields. And it’s been a joy to work with someone with that vision that’s allowed me to build the buildings of the quality, so it’s been a pretty good double act for most of that time.

I got on well with Mike because we’ve got such complementary skills. Mike’s a visionary, he has ideas. The hardest challenge for me is to get something built before his ideas changed. But once he’s had an idea and he’s said, ‘That’s it, we’ve signed somebody’, then I’m pretty much on my own. I’ve had the autonomy to then go and deliver those buildings. He’ll always come back and need to change something or have a tenant that wouldn’t normally fit, but we make them fit, and the challenges don’t stop. But because I’m sort of from a technical background and personally just love building things, it just worked very well with Mike. The most difficult times are when Mike’s got too long to think about something and then we can chase our tail a little bit.

Momentum

We had massive momentum as soon as we started the RBS building and the Civil Justice Centre then Halliwells, and then we had to move the Guardian Media Group, we had a hell of a lot to do. Certainly, it was more difficult from 2009 to 2012. But 2009, 2010, 2011, were still massively busy. There was never a day that I came into the office without my head spinning knowing what we needed to do. 2012 was a quieter year. We had worked on Manchester House, we had done The Avenue North, which was starting to trade successfully, and I guess it was only a few months around 2012 before it took off again. And then it took off at a pace. We funded XYZ speculatively and then we managed to fund No1 Spinningfields just off a 50,000 sq ft prelet. So, the momentum only probably only ran out of breath for a few months in that entire period.

Favourite building

I have favourite buildings for different reasons. I like 4 Hardman Square because of this lozenge shape, it almost looks like one of those American airstream caravans. Foster uses anodised aluminium in a raw state not a coloured state, so I’ve always liked that and also it’s built above the prisoner loading bay for the Crown Court so there’s an area of the building just behind the glass wall that’s actually the Crown Court prisoner area which not a lot of people know about.

I love 1 Hardman Street, the MediaCom building because of the speed that we concluded the deal and the build. We had 15 months from meeting them to design it, get planning, build it and fit it out.

And 3 Street because of the construction. We probably built faster than has ever been done in Britain to build an office building. When Mike asked me when I could finish the building, I said June 2009. He said ‘No, we have to have it done by June 2008 to sign Barclays’ and we were literally chasing the demolition machine across the site with the piling machine trying to divert services at the same time. A lot of sleepless nights but we did the 360,000 sq ft in something like 21 months and, during that time, we got Bank of New York in the building and that’s changed the building design drastically because they wanted to back it all up to work 24/7 American style. All the mechanical supplies, the lifts, the power, huge generators, rotary UPS (uninterruptible power supply) generators. The idea that they could work for three days without going home for food and water if there was a siege, we changed the building drastically and we still handed it over early. In January 2008, we were still in the ground and we handed the whole building over in August.

As Spinningfields matures, Manchester is turning its collective gaze to St Johns, the old Granada studios area over the road, to see if Allied London can repeat or even surpass the success of the past two decades on its next major project.

Great storey and fantastic piece of strategic development by Allied London believing in the city and putting their proverbials on the block – enjoy the rewards!

By Bday

Their vision and that of MCC has put Manchester in another league to other regional cities.£200 million pounds for an office block in Spinningfields says it all.That sum will no doubt be dwarfed when St Johns is built.Manchester needs a transport infrastructure to match its ambitions now.The Metrolink will soon be neither use nor ornament at rush hour.

By Elephant

Many will disagree with me, but I think Allied London and Spinningfields is one of the best things to happen to Manchester in recent times…well done to all involved.

By coolmanc

A great development, just a shame neither of the 2 previous designs for No.1 Spinningfields made it and that the old Daily Mail building was lost.

By Logenberry

Brilliant Scheme. All glass and no bricks!

By Sid Pilkington

Well done, Graham. What next?

Nigel Bruce

By Liverpool City supporter

Spinningfields is an excellent addition to the city – need more green/trees within it, but an amazing high-end space that Manchester can be proud of

By Ruby Jones